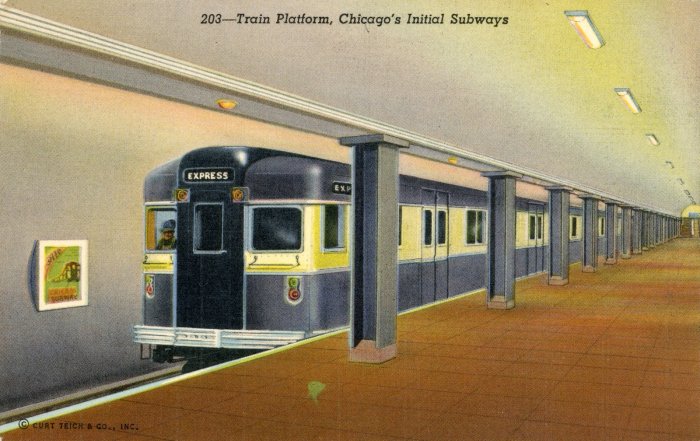

Artist’s rendering, from a 1940 Postcard, showing a BMT Bluebird rapid transit train running in Chicago’s subway, then under construction

In 1938, when FDR’s public works czar Harold Ickes (head of the New Deal agency PWA) decided Chicago would have two subways instead of just one, this presented a bit of a problem. After all, the Chicago Rapid Transit Co. only had 455 (or, depending how you count them, 456) all-steel rapid transit cars- enough to get the State Street tube started, but not enough for Dearborn-Milwaukee as well.

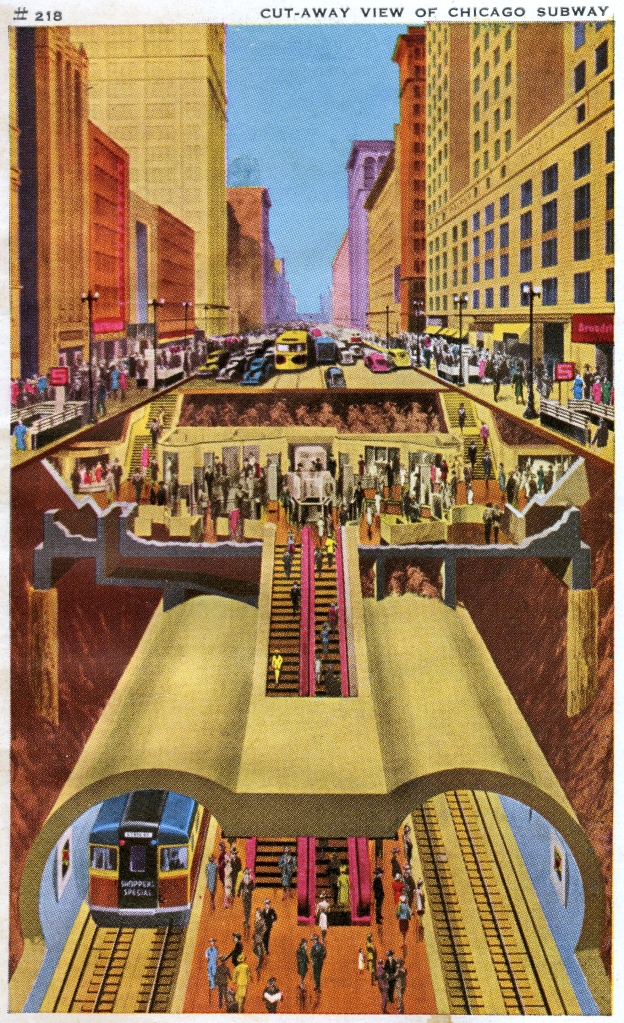

Circa 1940 postcard: “Cut-away view of Chicago’s subway in the Central Business District. Shown are the main tubes; the downtown center platform, which is 3500 feet long; the two-way escalators to the mezzanines with store connections; and the State St. surface level. Features of the subway are ventilation, illumination, escalators, safety, comfort.” The Bluebird-type subway car is a “State St. Shopper’s Special.” (Author’s collection)

Ickes had overruled Chicago Mayor (and political rival) Ed Kelly’s 1937 plan for two east-west downtown streetcar subways for a revival of the Dearborn-Milwaukee plan, which dated back to the 1920s. Ickes solved the problem of what to connect this second subway with by routing it to the west in the median of the Congress expressway. You can trace the origins of that highway back to the 1909 Burnham Plan, but more as a boulevard, since there were no cars then capable of driving highway speeds. Kelly had wanted many of the west side “Ls” to be converted into New York-style elevated highways with buses running on them, except for the Garfield line, which would have been saved. Instead, the opposite happened. Garfield was transformed into the Congress line and the other “Ls” were kept.

The Illinois Commerce Commission ordered CRT to obtain 1000 new modern steel subway-L cars in 1939 by any means necessary, but the bankrupt private operator had no funds to do much more than to make a full-scale car mockup. As a backup plan, Ickes had the subways engineered so they could have been operated by bus. The newest L cars were the 4000-series, the last of which was built in the early 1920s by defunct Cincinnati Car Company. Where to get new inspiration from?

New York’s BMT (Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit) had a new three-section articulated car under development- commonly called the “Bluebird” but officially “Compartment Cars,” the first PCC rapid transit cars. Top speed was only 42mph but with rapid acceleration. BMT expected to use them as fast locals that could keep up with older, slower cars used in express service. Chicago was certainly impressed, showing Bluebirds as they would look running in the subways once finished. Newsreel footage of the Bluebird prototype made it into the promotional film “Streamlining Chicago” (http://vimeo.com/30568829) and the Bluebirds were the obvious inspiration for the first 5000-series L/subway cars here, built in 1947-48. (Not to be confused with the current 5000-series cars with AC propulsion and transverse seats.)

But like the 5000s, New York’s Bluebirds had a somewhat disappointing career. BMT had ordered 50 Bluebirds from Clark Equipment Company, supplier of PCC parts, but the City of New York took over the BMT in 1940 and immediately tried to cancel the contract. (BMT had intended to use them on many elevated lines that the city decided to tear down anyway.) Clark had completed five sets and NY had to take these. This meant only six sets in all, if you include the prototype that never had couplers installed.

The Bluebirds, as oddball equipment, lived out their service lives on the BMT Canarsie Line and the Franklin Avenue Shuttle, before being scrapped in 1956. Chicago’s four experimental 5000s had a somewhat similar fate, being relegated to occasional use before finally being assigned to the Skokie Swift in the mid-1960s. Chicago did not open the Dearborn-Milwaukee subway until 1951, and then only after receiving the initial order of 6000s, which were very much more successful cars than the Bluebirds or the 5000s ever were.

-David Sadowski

Tribute to the BMT Bluebird

A 3-section “Bluebird” at left in 1956, just prior to scrapping, with a Budd 5-section prototype from 1934-5 awaiting a similar fate (R. E. Jackson photo)

Fresh Pond Yard, Queens, April 22, 1956 (Author’s collection)

A similar scene but in color.

Fresh Pond Yard, April 22, 1956. (Photographer unknown)

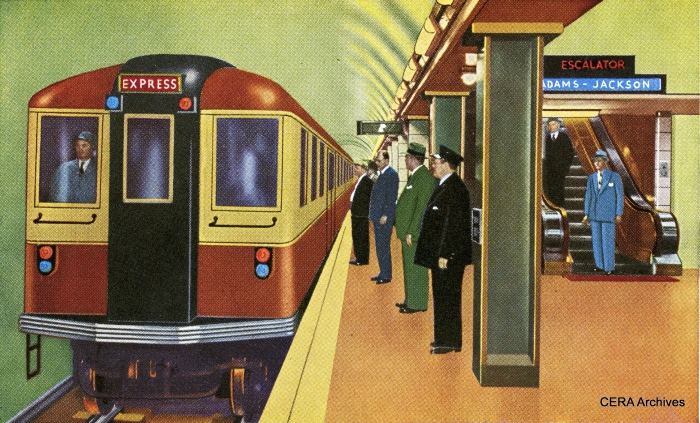

A fanciful 1944 view of Chicago’s new State Street subway, patterned after a famous 1943 photograph, but showing a BMT-style “Bluebird” in red.

BMT “Bluebird” prototype at the Clark factory, 1939

February 7, 1939 – Press release from Cal Byoir and Assoc.: “Trucking” in Rubber. Trucks which carry new BMT subway cars, work on which is being rushed at Battle Creek in preparation for New York debut in March, are result of six years scientific research. Rubber “sandwiches,” which support steel tires or wheels, and rubber springs were produced in B. F. Goodrich Company research laboratories. Other features of car, which telescopes full quarter-century in rapid transit industry, include streamlined aluminum body, green mohair seats, plate mirrors and air-conditioning. Workmen are shown making field inspection at preview. (Editor’s note: These cars did not have air conditioning, but they did have forced air ventilation. This picture (by an unknown photographer) was taken at the Clark Equipment Co. plant.)

CRT/CTA 5004, shown here in 63rd St. Lower Yard, on a 1963 CERA fantrip (Author’s collection)

The “other” Bluebird PCC rapid transit cars- Cleveland’s, built in the mid-1950s, are shown here in this photograph by the Author, just prior to their retirement in the early 1980s.