It’s a curious thing to write in your high school yearbook, that you hope to “live long enough to ride the Chicago Subway.” Nowadays, a subway ride is pretty trivial, one of life’s commonplace occurrences if you work downtown and ride the CTA- something we all take for granted. But you have to consider the context. It was something my Dad said in 1942, when the US had just gotten into WWII and Chicago’s subways were still under construction.

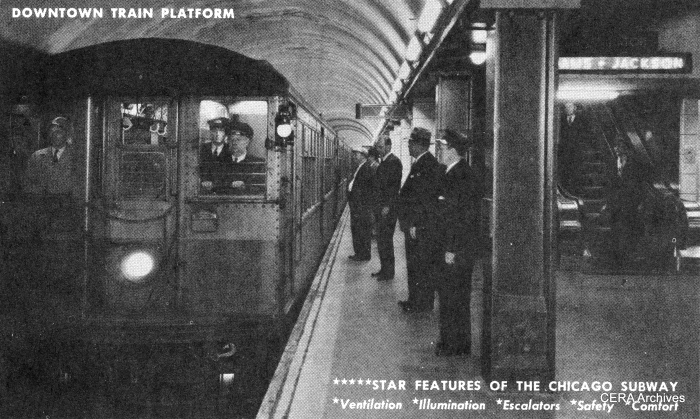

A Chicago family, all dressed up for their first subway ride, in October 1943.

From the 1942 Steinmetz High School Yearbook.

As things turned out, my Dad’s fears that he might not live long enough had some justification. He turned 18 in October 1942, soon after graduating from Steinmetz High School, on the city’s northwest side. He was then drafted and inducted into the Army Air Force in April 1943, and served in the Pacific as a radio operator before being honorably discharged in 1946. He did get to ride the subway, but it may have taken a while.

Chicago’s first tunnel, the State Street tube, opened for revenue service on October 17, 1943, shortly after my father’s 19th birthday. His older brother Frank enlisted into the Army and became a Medic. He was killed in action on on April 19, 1945, during the battle of Okinawa. I don’t know if he ever did get to ride in the Chicago subway.

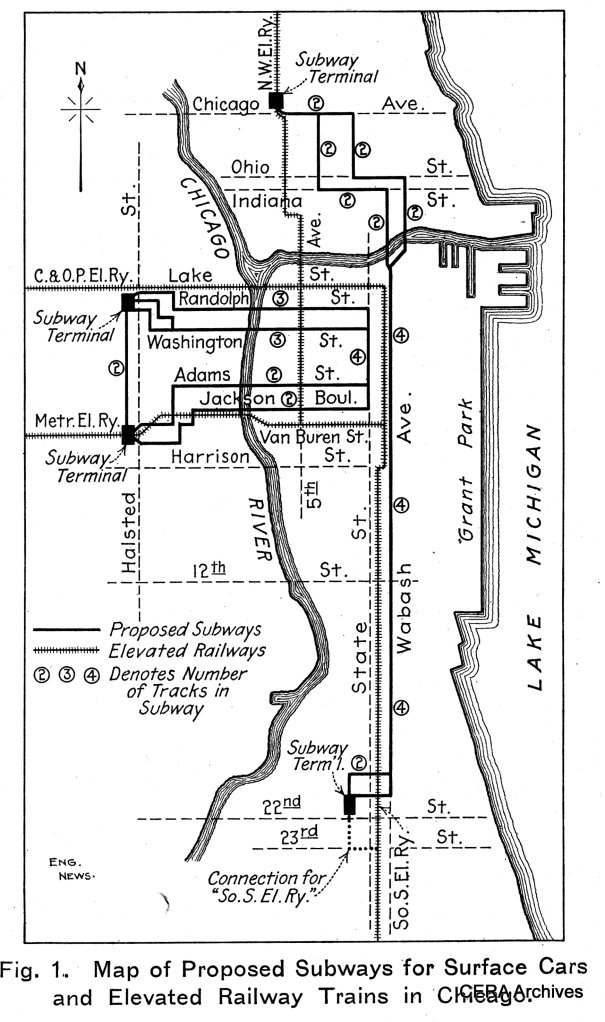

Chicago’s “Initial System of Subways,” which broke ground in 1938, had been in the works for a long time. According to the June 3, 1909 issue of Engineering News:

The idea of building subways for rapid transit purposes in the business district of Chicago is an old one, and has been embodied in a number of rapid transit schemes put forward by the municipality and outside interests during the past 20 years, or more.

Thus, by the time construction began on an actual subway in Chicago, the topic had been discussed for 50 years, and had become something of a civic joke. Many people doubted it would ever be built.

Yet even in 1908, barely a decade after the creation of the Union Loop connecting Chicago’s four rapid transit companies, the need for a subway was clear. The Loop “L” became congested right away, to the point where newspaper editorials called for action to be taken to alleviate even before constructing additional outlying lines.

While the Loop “L” is still with us after more than 115 years, there were calls early on to get rid of it. Again, from the 1909 Engineering News article:

In most (if not all) of these schemes the object has been to relieve traffic congestion in the streets by removing the street cars (or a large proportion of them) from the surface, and not to establish an underground railway independent of the surface facilities (as at New York). In the recent plans, this system is extended to include the trains of the elevated railways. It has been suggested that if all these trains can be accommodated in the subway, in addition to the surface cars, the unsightly and in many ways objectionable structure of the elevated terminal loop may be removed from the crowded streets of the business center. This, however, does not appear to be probable.

By 1905, the city’s newspapers were looking to through-routing of the rapid transit lines as a way to relieve congestion on the Loop “L”. The rapid transit companies resisted. In time there would be some through-routing on the “L”, but a subway would naturally provide through-routing since it would connect two lines.

In these early plans, we already see the idea present that the north-south subway would function as an “express,” with a limited number of stops, while the existing elevated would be a “local.” The State Street subway, as built, functions in just such a way.

The 1909 Engineering News piece also notes:

The subways now proposed (as described above) would constitute the beginning of a comprehensive system, to be developed as the growth of the city may require. The report states that these alone cannot be expected to provide adequate transportation for any considerable future period, and that their construction must be followed (at an early period) by subways taking advantage of other outlets from the business district.

This notion also carried along into future plans. The 1938 subway plan approved by Harold Ickesand his Federal agency the PWA (Public Works Administration) was meant to be just the first phase of a much larger subway system, with lines radiating out to all parts of the city.

By the 1920s, the city’s rapid transit subway plans had evolved to two north-south tubes running along State (always intended to be the first built) and either Clark or Dearborn. The State tube was always intended to connect back up with the North-South “L”, but what to connect Subway No. 2 up with was not as obvious. Sure, on the north end, it made a lot of sense to run northwest along Milwaukee Avenue to connect up with the Met “L”, but on the south end, things were not as certain.

Plans called for a southwest subway line, but this remained an unrealized dream until the opening of the CTA Orange Line in 1993. So, what to connect Subway No. 2 to instead?

An answer eventually developed along with plans for a west side super-highway. In 1937, Mayor Kelly proposed that the city build a number of west side elevated highways. Most of these would replace existing elevated rapid transit lines. In this plan, the Lake Street, Douglas Park, and Humboldt Park “L” branches were to be turned into elevated highways with express bus service. In actual practice, this would have been much like New York’s West Side Elevated Highway. The only west side line that would have remained was to be the Garfield Park “L”.

Not everyone liked this plan, however. In particular, there were members of the Chicago City Council who did not like it. And Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes did not like it.

The 1909 Burnham Plan of Chicago envisioned expanding Congress Street into a west-side boulevard. As there were few autos in 1909, this would not have been an expressway as we know it today. But the idea persisted, and land speculators had bought up property along the route in anticipation of quick profits that did not come.

In the 1930s, the notion of a Congress Street Super-Highway took hold. But a primary obstacle to constructing it was the Garfield Park “L”, which already occupied part of its intended route. The idea of relocating the rapid transit line into the expressway median was a natural progression. (But not an original one- in 1940, part of a Pacific Electric interurban line was relocated into the median of the Hollywood Freeway through Cahuenga Pass. This service was abandoned in 1952.)

The Congress rapid transit line opened in 1958, finally connecting to the Milwaukee-Dearborn subway twenty years after the latter began construction. The Milwaukee-Dearborn subway had opened in 1951, having been delayed for many years by WWII and a shortage of steel rapid transit cars to operate it. From 1951-58, service terminated at LaSalle and Congress.

How to pay for the subways? For many years, the City of Chicago amassed a ‘transit fund’ in the millions from a portion of the proceeds of the Chicago Surface Lines streetcar system. Ground was almost broken on the State Street tube in 1931, but was derailed by lawsuits from landowners along its path, who objected to being taxed to help pay for it. Then, the Depression hit full force.

The Cermak administration borrowed from the transit fund, replacing dollars with tax anticipation bonds of dubious value. This created a shortfall that made subway construction impossible, until the Federal government agreed to fund a portion of the cost as a back-to-work project. The PWA share essentially replaced the amount lost by the city’s borrowing.

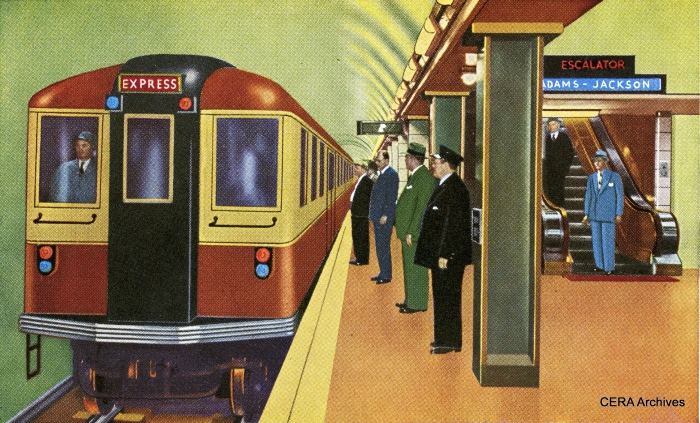

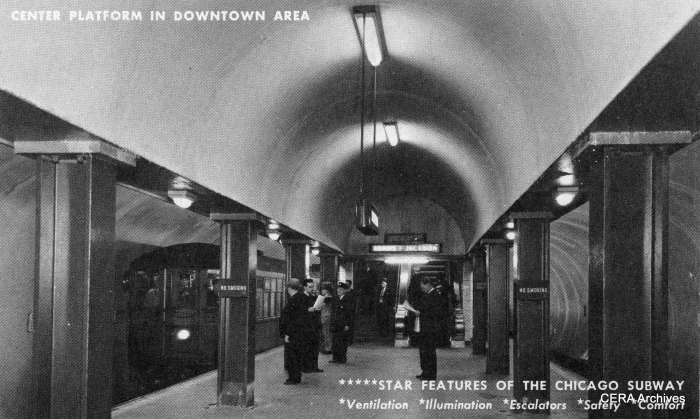

The Chicago subway, as built, was a classic example of “Art Moderne,” (also called Streamline Moderne) and was to some extent influenced in style by other contemporary subways such as theLondon Underground and the Moscow Subway. You can read a very interesting article about Art Moderne in the Chicago Subway here.

For the City of Chicago, building the subways helped bring about the dream of transit unification between the surface and rapid transit systems. This was somewhat analogous to how building theIND Subway helped bring about transit unification in New York City.

The difference is that New York not only built, but operated the IND in direct competition with the privately-owned BMT and IRT lines, eventually forcing them to sell out to municipal ownership. Until 1943, Chicago hoped to unify Chicago Surface Lines and Chicago Rapid Transit into a new private company, which probably would have been called the CTC (Chicago Transit Company).

While technically both systems were bankrupt and under the control of the courts, in actual practice, the overall condition of the rapid transit lines, which accounted for less than 20% of all passenger traffic, was much worse than the surface system. This derailed every attempt at unification, since the high cost of modernizing the rapid transit system id not allow room for making a profit. Unification was only realized after the city gave up on the idea of a new private company in 1943 and embraced the idea of public ownership. The Chicago Transit Authority was created by an act of the State Legislature in 1945 and assumed control of CSL and CRT in 1947. It took another five years to add the Chicago Motor Coach Company to the fold.

None of this had been resolved in 1938, when Ickes and the PWA approved the plan to build Chicago’s Initial System of Subways. PWA did not want to build the subways if there would be no operator to run them, and CRT was just barely able to collect enough revenue to pay for current operating expenses.

As a safety measure, the City had decided that only steel cars would be allowed in the new subways, fearing that wood cars would increase the risks of fires and deadly accidents such as New York’s infamous Malbone Street Wreck. CRT had only 455 steel cars in its fleet (or 456, depending how you count them).

It was estimated that 600 modern cars with quick acceleration would be needed to run the State Street tube to capacity. CRT had no resources to buy new cars, but could at least get service going in the north-south subway by using every available steel car it had. It was not optimum but it would have to do.

The PWA pressed the City to make a commitment to achieving transit unification by 1942. At the same time, they made sure that the Chicago subways were engineered in such a way that they could have been operated using buses as a last resort.

As things turned out, it was determined that operating the State Street Subway did not materially change CRT’s financial position. They experienced both increased costs and revenues as a result, and these tended to cancel each other out.

Digging the tunnels downtown was akin to a complicated mining operation, and also undermined the old Chicago Tunnel Company system, which was already in a decline. The subway leveraged the earlier tunnel construction in two ways, expanding out from existing tunnels, and using the tunnel system to haul away the blue clay as it was excavated.

Building the subway under the Chicago River was an even more daunting challenge, and required much ingenuity to solve.

By 1941, even before Pearl Harbor, the United States was in the midst of a large-scale defense buildup. Materials needed for subway construction came under government control. By mid-1942 the two subway tunnels were 75-80% completed, but work was halted on the Dearborn-Milwaukee segment for the duration. After all, there was no chance to get the new rapid transit cars that were required to run it.

The State Street tube was allowed to be completed and opened in 1943 as an aid to defense workers getting to and from their jobs helping the war effort. Wartime restrictions were lifted from the Dearborn-Milwaukee subway late in 1945, but service did not begin until 1951, as new 6000-series PCC “L”-subway cars were delivered to CTA.

2013 marks the 70th anniversary of the opening of the State Street Subway. It is an important part of Chicago history, and one which all Chicagoans can be rightly proud of. The story of the Initial System of Subways is a fascinating one, which we will return to in future blog posts.

-David Sadowski

An early subway plan from 1909. The idea of an east-west subway for streetcars (and later, buses) persisted for another 50 years but was unrealized. Instead of a 4-track subway on Wabash, two tracks each were built on State and Dearborn.

A colorized version of the 1944 postcard photo above, but with a more modern rapid transit car in place of the 4000s. It looks much like the New York BMT’s “Bluebirds,” then the state-of-the-art. They were the first elevated-subway cars to use PCC technology, and helped inspire the four 5000-series articulated units CRT ordered after the war.

An aerial view (looking east) of the Garfield Park “L” and the future site of the Congress Super-Highway on September 2, 1950. If you look closely, you can see that some demolition has already taken place. The highway follows the path of the “L” in the foreground, heading straight through the middle of the old Main Post Office in the background.