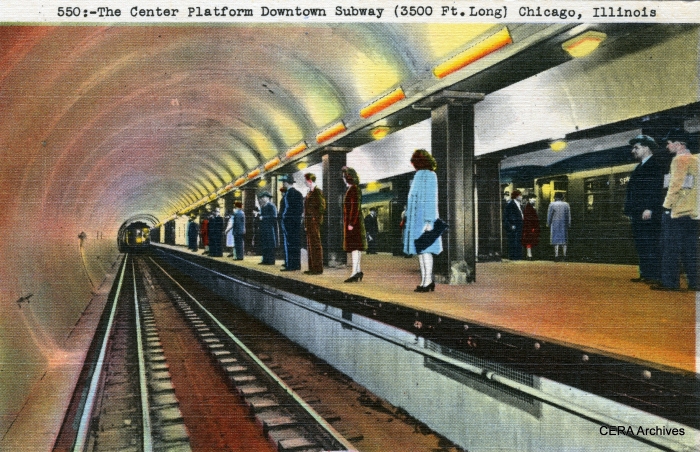

A “colorized” version of one of the Chicago Subway postcards from our earlier post. 3-D glasses not included.

Today we take up where we left off in our earlier post about the building of Chicago’s “Initial System of Subways.” We now tend to take the subways for granted, but there was a time when they were quite newsworthy.

Apparently some portion of the new subway was dug out by hand using long knives, in much the same fashion as the old Chicago Tunnel Company system of decades before.

Chicago’s Subway Being Dug With Knives

Chicago- Because Chicago’s subway is being dug at a depth of 35 feet, where there is clay instead of rock, it is being dug with knives. A curved blade about a foot long, with a handle at each end, is held by two men while a third pushes the knife downward to slice off a long strip of clay. A carload of the stripped clay is shown above being taken from the tunnel. (January 10, 1939)

Chicago Builds a Subway

Hailed as the most pretentious civic undertaking since Chicago shook off the ashes of the Great Fire, a $40,000,000 subway system is being tunneled beneath the city. Sandhogs are digging at a rate of 30 feet a day and should reach the end of the first unit –7.5 miles- of tunnel by July 1, 1940. This picture shows a subway worker hauling out a load of clay in the subway dump train. (August 27, 1939)

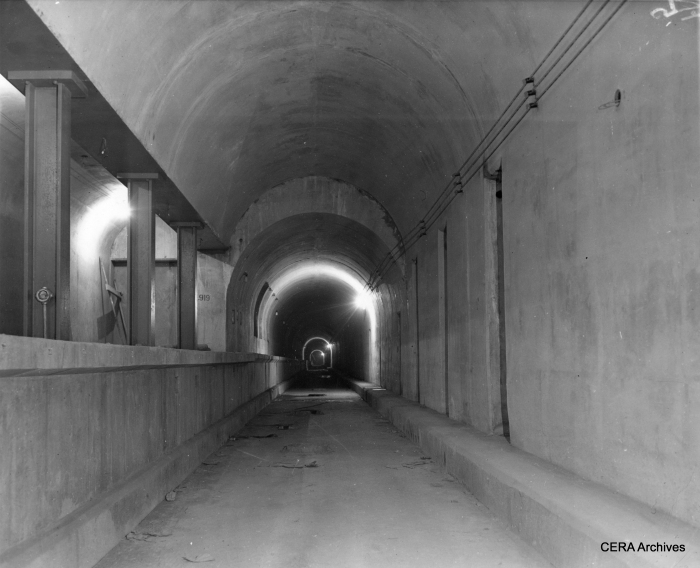

There could be a long wait for the next train, especially since the tracks haven’t been laid yet.

Chicago Gets a Subway

Chicago- The dream of Chicago officials for years– a subway system to relieve traffic congestion around the Loop– is rapidly approaching reality. Here are several views of the city’s new subways as they appear today, well on the way toward completion. Wartime priorities may delay the opening, however, since steel needed for rails and cars must be used to arm America instead. Mrs. Leroy Post, left, and Mrs. C. L. Mann, right, both of Evanston, pictured in this view of the State Street tube hope to be able to board a train at this platform someday, however. (January 31, 1942)

Except for rails, this section of the State Street line of Chicago’s new subway system is virtually completed. At the left is part of the Clybourn-North Avenue station platform. (January 31, 1942)

This partially-completed subway lies under the Chicago River and is the first part of the State Street line. Workmen at the left are installing conduits for third rail power distribution. (January 31, 1942)

Escalators will save Chicago’s subway riders the task of walking up long flights of steps. A future subway strap-hanger shown here doubtless wishes the escalator at the right was completed instead of being only framework after trudging up the temporary steps at the left. (January 31, 1942)

A future subway rider tries out the temporary station control equipment at a station on the State Street line. Soon he and thousands of other Chicagoans will be dropping coins into turnstiles such as this for their underground ride. This and other stations will have structural glass columns, concrete floors scored in a tile pattern and fluorescent lighting. (January 31, 1942)

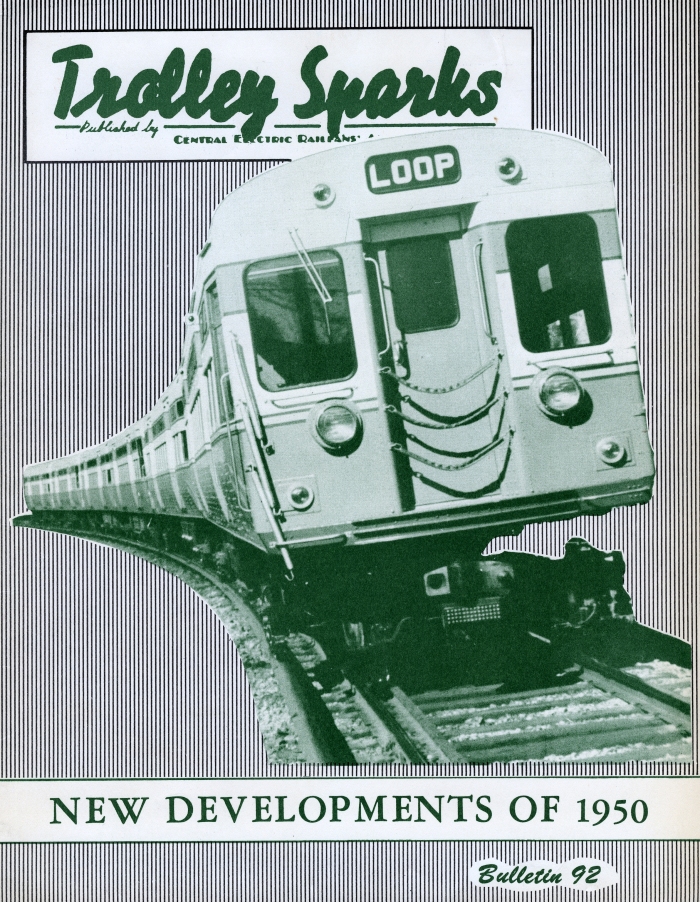

The new CTA 6000s were featured on the cover of CERA Bulletin 92, as one of the “new developments of 1950.”

Read CERA’s 1950 article introducing the 6000s here as a PDF file.

Here come the 6000s.

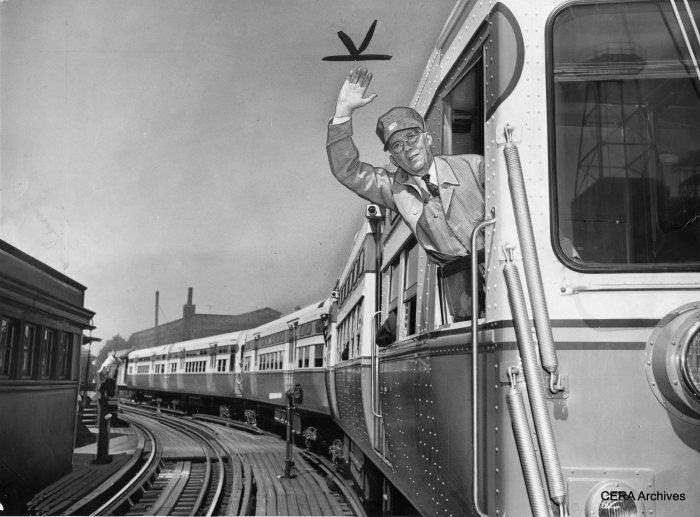

CTA Trial Run, New Train Gets the Highball

Motorman Charles R. Blade, 59, of 1740 Grace, who is with the company 39 years, looks out of his cockpit. He is ready for return trip downtown, pix taken at Logan Square Terminal. (August 16, 1950)

Changes

While the State Street subway opened in October 1943 using 455 4000-series steel “L” cars, the newest of which were already 19 years old, the Dearborn subway got brand-new equipment. CTA ordered 130 new 6000-series PCC rapid transit cars in 1949, and began taking delivery on them the following year. This was considered the number needed to operate the Logan Square and Humboldt Park lines via the new Milwaukee-Dearborn subway. However, things did not work out that way.

Shortly before the new subway opened on February 25, 1951, the CTA Board voted to discontinue service on the Humboldt Park branch, which was deemed unworthy of receiving new 6000s. Humboldt Park riders were encouraged to ride the North Avenue trolley bus instead, a rare instance of CTA giving precedence to the surface system over the rapid in this era. Neighborhood opposition succeeded in saving the line from abandonment for a time, but only as a shuttle operation using some of the oldest equipment on the CTA system. Predictably, the inconvenient shuttle was short-lived and service on the Humboldt Park branch ended on May 4, 1952.

Similarly, while the junction between the new Milwaukee-Dearborn subway and the old Paulina Met “L” was intended to be permanent, not temporary, CTA decided to discontinue service on the “L” portion as soon as the subway opened. This is understandable, since the subway provided a much shorter and direct path downtown. However, it would have been possible to continue Humboldt Park service downtown via the old routing, while Logan Square trains used the subway.

To do so, however, would have complicated Garfield Park service over the temporary ground-level Van Buren Street trackage that was used from 1953-58. One reason for opening the Milwaukee-Dearborn subway, even as a stub-end line terminating at LaSalle Street, was to reduce the number of Met “L” trains that would have to use the temporary trackage. Eventually, CTA found it only needed 80 6000s to operate Milwaukee-Dearborn. In late 1952, even these were shifted away to the much busier State Street subway, and Logan Square received the older 4000s instead.

Meanwhile, CTA did not tear down the Paulina “L” structure until 1964, leaving it as a single-track service connection that was traversed by at least one CERA fantrip. And only half of the Humboldt Park branch was demolished right away. Supposedly, the remaining portion would have been used as a storage yard for Chicago Aurora and Elgin trains, if service had been resumed downtown.

In this scenario, CA&E steel trains (the woods were not allowed) would have been routed through the Milwaukee-Dearborn subway, since the Interurban had lost its downtown terminal.

The City of Chicago dedicated the new subway at the Washington station on February 24, 1951. Dignitaries included Mayor Martin H. Kennelly, Commissioner of the Department of Subways and Superhighways Virgil E. Gunlock, CTA Chairman Ralph Budd, Chief Engineer Dick Van Gorp, General Manager Walter J. McCarter, and Aldermen Joseph Rostenkowski, Clarence P. Wagner, and James F. Young. TV cowboy Monte Blue was also on hand.

Mayor Kennelly (1887-1951) is not as well-known by any means as the man who replaced him, Richard J. Daley, but he did serve two terms from 1947-55 and thus bridged the Kelly-Nash and Daley eras. Conventional wisdom says he was a reformer who found that Chicago wasn’t ready for that much reform yet.

Chicago Mayor Martin Kennelly is the first one off the train of new 6000-series “L”-subway cars.

Chicago Mayor Martin Kennelly is the first one off the train of new 6000-series “L”-subway cars.

Virgil Gunlock, then head of the City’s Department of Subways and Superhighways, addresses the crowd. I’m not sure if this was before or after the cowboy.

Virgil Gunlock also appears in our blog post The Great Subway Flood of 1957.

Mayor Kennelly at the opening of the Dearborn-Milwaukee subway on February 24, 1951. Both subway tubes were dedicated during mayoral election campaigns.

By the time the Milwaukee-Dearborn subway was finally connected to the new Congress expressway median line in 1958 (which replaced the old Garfield Park “L”), Chicago had a different Mayor.

A CTA test train of 6000s in the brand new Congress Expressway median line on June 18, 1958, a few days before regular service began.

In the June CERA program, we saw some of Bill Hoffman’s movies, including the free rides given on a portion of the new CTA Congress rapid transit line on June 21, 1958, between Halsted and Cicero. Perhaps not coincidentally, this was the very same day that the last streetcar ran in Chicago.

You’re invited…. to the dedication of the new West Side Subway in the Congress Expressway median strip with Mayor Richard J. Daley officiating, June 20…. to take a free train ride and inspect the new subway on June 21…. to use the fast, traffic-free regular service which goes into effect at 4:00 A.M., Sunday, June 22. V. E. Gunlock, chairman of the board, Chicago Transit Authority, and Miss Julia Riordan, a stenographer in CTA’s Public Information Department, inspect the posters at Keeler avenue staton announcing these events. Posters will be displayed at all rapid transit stations starting Monday, June 9. (1958)

Within a few short years, however, not all the news was good:

The Chicago Subway as it looked in 1965.

Empty Chicago Subway Station

This subway station in downtown Chicago was practically deserted when this picture was taken at 9 p.m. last night. A recent outburst of subway beatings and robberies has alarmed Chicago’s commuters. The subway situation leaped into prominence Jan. 7 when a law school dean and state legislator was beaten and robbed by three toughs as 20 other passengers watched. (1965)

But Chicago’s subways have rebounded from these low points and even survived the Great Chicago Flood in April 1992. Photographing subway trains is not the easiest thing to do, so we will leave you with a shot of a 6000s pair taken in April 1988.

-David Sadowski

A two-car train of 6000s in the State Street subway in April 1988. (Photo by David Sadowski)