Chicago’s first subway opened 71 years ago, during World War II. But the planning for subways goes back at least 30 years earlier.

We received a call the other day from Beverly Petzhold, the widow of Charlie Petzhold. Charlie was well known to the CERA community and frequently gave “newscast” updates at meetings on various projects he was working on for the CTA as an engineer. Sadly, he passed away 20 years ago.

Mrs. Petzhold has generously donated Charlie’s collection of historic documents to the CERA Archives. Many of these detail the planning, engineering and construction of the Chicago subways over the decades. We took note of her gift here.

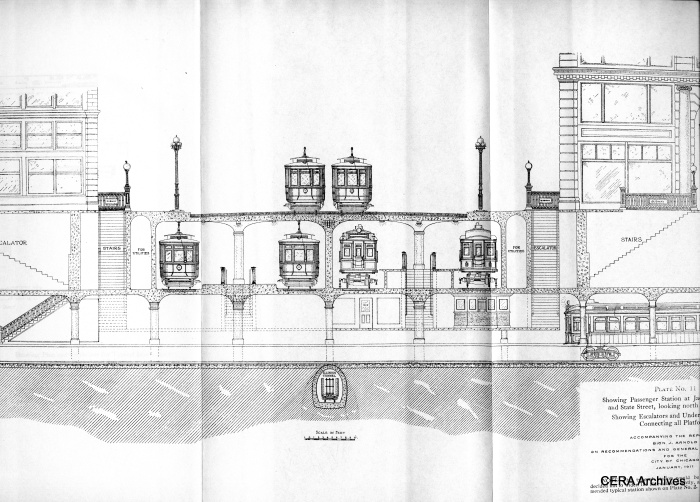

Mrs. Petzhold found another book to add to our collection- General Plans for a Passenger Subway System in Chicago by Bion J. Arnold, published in January 1911.

It’s instructive to consider the life and career of Bion J. Arnold, who is largely forgotten today, but was a giant in the transportation field in his time. Arnold was involved in designing the very successful IRT subway in New York.

Following this he acted as a consultant to various cities in developing their own plans for subway construction. It is not Arnold’s fault that many of these plans became mere pipe dreams for a long time. As he wrote in his introduction to the Chicago plan book:

No attempt has been made to show in this report the necessity for subways, for it is taken for granted that on account of the present congestion, at times, of the surface line cars and elevated trains in the business district, as well as the apparent demand for the removal of the elevated loop structure, that subways are desired regardless of whether they can be justified from a financial standpoint or not.

Arnold also noted that the existence of the Chicago Tunnel Co. freight system complicated the routing of new subways, as most of the tunnels were at a depth of 33 feet (this in spite of the title of Bruce Moffat’s book Forty Feet Below). As things turned out, during actual construction, the freight tunnels were used to remove excavated materials, so they were a benefit. But since the new tunnels bisected the freight system in many areas, they hastened the decline and eventual demise of the system.

Less than a generation after the completion of the Chicago Loop “L” structure in 1897, there were calls to remove it and replace it with subways. These plans influenced civic planning all the way up until the administrations of Mayors Michael Bilandic and Jane Byrne in the late 1970s.

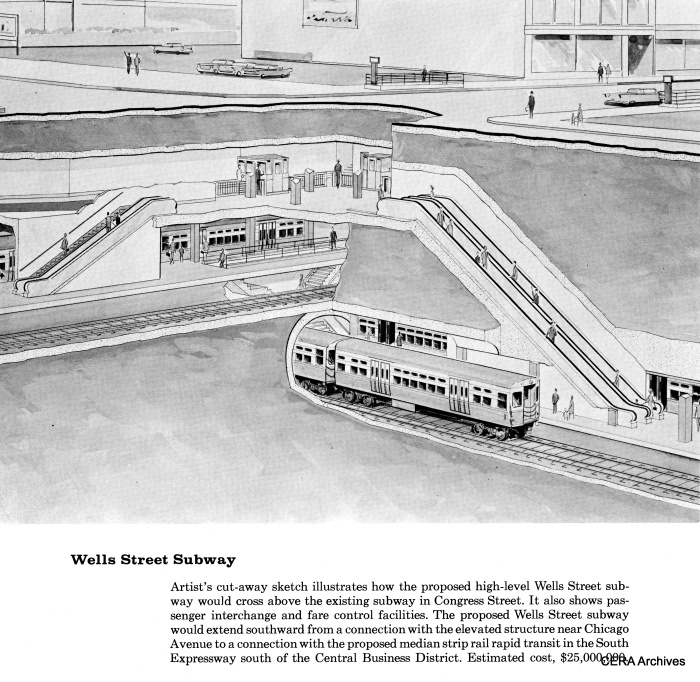

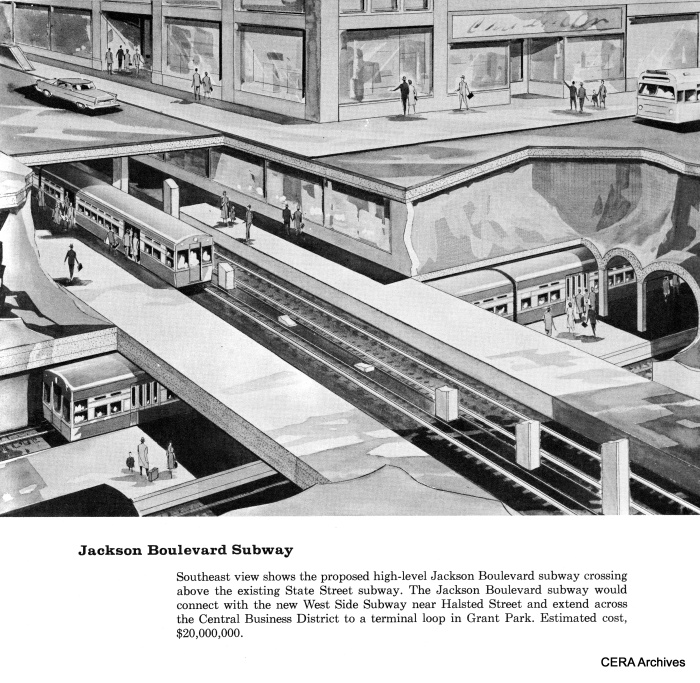

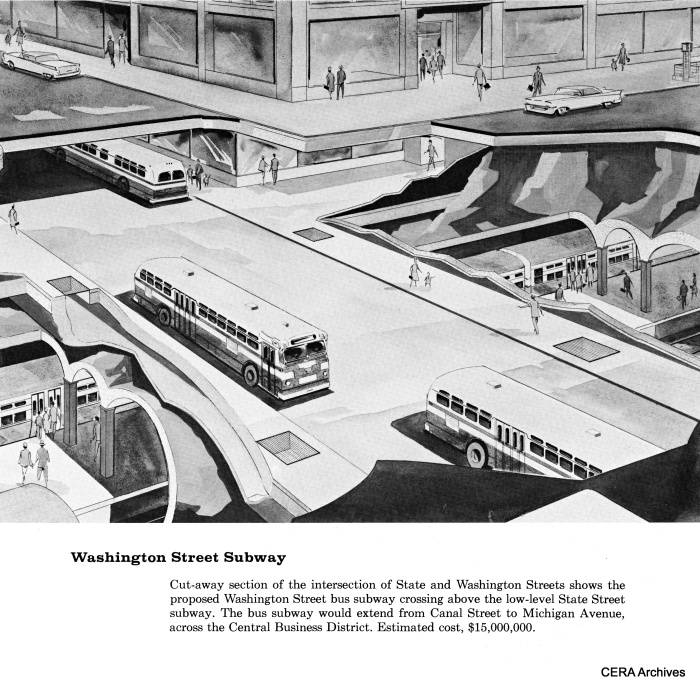

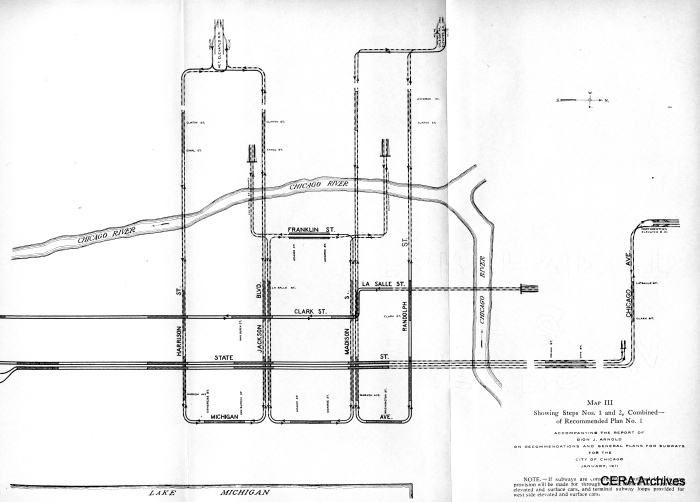

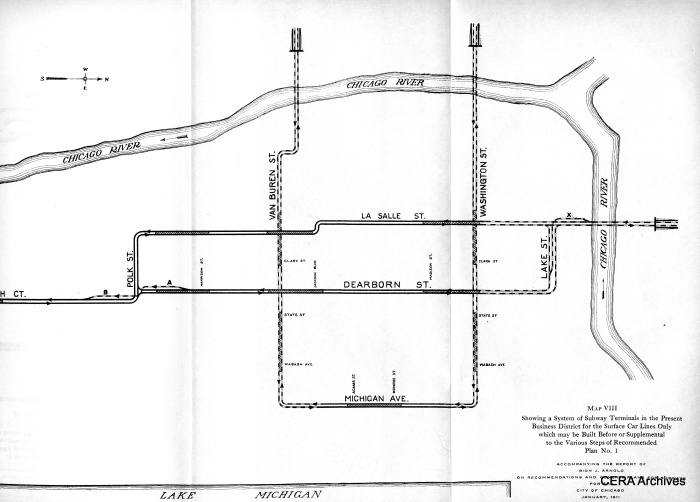

The perceived need to replace the Loop “L” in stages had a major influence on these subway plans. In a similar fashion, the existence of streetcar tunnels under the Chicago River strongly influenced plans for Downtown streetcar subways. These plans even outlasted the streetcars, since the CTA and City of Chicago were still hoping to build just such a bus subway along Washington Street into the 1960s.

Although many changes were made in the Arnold plan for Chicago subways, you can draw a straight line between those plans, and what was eventually built.

Since the Loop “L” connected with lines going to the north, south, and west, any subway that hoped to replace the Loop would have to go in these same directions. North and south could be through-routed and State Street was quickly identified as the prime location for Chicago’s first subway. Construction almost began in 1931, but was halted due to some lawsuits regarding funding and the Great Depression. But the project was revived, and with the addition of Federal aid through the PWA, actual construction started in 1938, and the subway opened in 1943.

Connections to the Lake Street and Metropolitan “L”s to the west would have to contend with Lake Michigan on the east, and the Arnold plan envisioned a subway under Michigan Avenue connecting them. Portions of this rapid transit subway were intended to run side-by-side with streetcars, for a total of four tracks.

By 1937, the City of Chicago’s streetcar subway plans called for two underground turning loops east of Michigan Avenue. There also would have been an underground car barn. Although never built, these are the locations where underground parking garages later appeared.

By the mid-1920s, subway plans had evolved to where the Number 2 tube would have gone in Clark Street. On the south end, the plan was to connect to a new subway going off to the southwest. This side of the City did not get such service until the Orange Line “L” opened in the early 1990s.

In 1937, the City of Chicago, lobbying for Federal work project funds, issued a comprehensive plan for transportation, commonly referred to as the “Green Book.” This included the State Street subway and also the two east-west streetcar subways.

The PWA, under the direction of Harold L. Ickes, who also served as Secretary of the Interior, had other ideas. While accepting the necessity of the State Street tube, Ickes advocated for a second subway on Dearborn Street. This was a better location than Clark, since it permitted an easier transfer to State Street trains.

Ickes also preferred construction of an expressway along Congress Street, necessitating the relocation of the Garfield Park “L” into its median. Garfield/Congress trains would be routed into the Dearborn subway, which would then continue the northwest along Milwaukee Avenue to connect up with the Met Logan Square branch. Construction started in 1938, but wartime shortages delayed the opening of this second subway until 1951.

Even Samuel Insull had realized the advantages of a rapid transit line going Downtown along Milwaukee Avenue, in the 1920s, but if he had built it, it would have been an “L”. Subways were too costly, and would have to be built by cities.

The streetcar subways were put onto the back burner, but continued to appears in the City’s plans for years afterward. They were never built, but if they had been, it’s possible they would have facilitated the continued use of streetcars in Chicago, as they have done in other cities like Philadelphia, Boston, and San Francisco.

Even with two subway tunnels open by 1951, it was still not enough to allow for the razing of the Loop “L”, although it certainly did help reduce congestion. This would require additional subways. In final form, by the 1970s, there were plans for a Monroe Distributor that you can read about here. These plans were scrapped due to their high cost.

Thus Chicago’s Loop “L”, unloved and unwanted for much of its history, emerged as a survivor, and continues today as a cherished icon and landmark of the City. But the wheels that set that in motion began turning more than 100 years ago.

What became of Bion J. Arnold? Eventually, he controlled the Elgin and Belvidere Electric Company, which ran an interurban along 36 miles of track between those two Illinois cities. This venture failed by 1930, taking with it much of Arnold’s personal fortune.

But even that had a legacy, as several miles of the abandoned Elgin and Belvidere right-of-way are now owned by the Illinois Railway Museum, and are used as it’s Main Line.

-Ye Olde Editor

PS- The CERA Members Blog reached a milestone the other day with 943 page views, our most ever. This blog had 75,000 page views last year, and more than 100,000 so far this year. We expect that by year’s end, this total will probably exceed 115,000, an increase of more than 50% over 2013.

We take this to mean that we must be doing something right now and then. It is our hope that as more and more articles appear on the blog, it functions as an online archive and resource for transit history. We thank you for your continued support.

A rather fanciful early 1940s postcard, showing what appears to be a New York BMT "Bluebird" train in the Chicago subway. The four experimental articulated cars 5001-5004 (later renumbered 51-54, and not to be confused with the current 5000-series) were based on the Blue bird design and were delivered in 1947-48 (CERA Archives)

CTA Met car 2785 at Lake Transfer. At this long-demolished station, closed in 1951 with the opening of the Dearborn-Milwaukee subway, passengers could transfer from the Met “L” to the Lake Street “L”, which crossed below. In 1954, a direct connection was built at this spot, which is used today by the CTA Pink Line to reach the Loop. (J. R. Williams Photo – CERA Archives)

CTA 6001-6002 at Marshfield on the Garfield Park “L” circA 1950. The first batch of 6000s, which had flat doors, were ordered for use in the Dearborn-Milwaukee subway, which opened in February 1951. At this location, trains branched off in three directions, to Logan Square/Humboldt Park, Garfield Park, and Douglas Park. (J. R. Williams Photo – CERA Archives)